An ‘Ireland First’ Tax Code?

TCJA’s corporate offshoring incentives are anything but America First.

By Brad Setser, Whitney Shephardson Senior Fellow at the Council on Foreign Relations

President Donald Trump’s trade war has, likely unintentionally, brought the role of trade in facilitating U.S. corporate tax avoidance to light. As Congress debates extending existing tax provisions, this shortcoming needs to be fixed.

No industry matches the U.S. pharmaceutical industry when it comes to shifting profits on U.S. sales out of the United States. U.S. pharmaceutical companies, incentivized by the low tax rate on global intangible profits created by the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA), produce abroad in order to move profits overseas to avoid paying the headline U.S. tax rate of 21%. The threat of pharmaceutical tariffs led these companies to rush their most valuable medicines to the United States ahead of the tariffs. Pharmaceutical imports jumped to $110 billion in the first three months of the 2024, almost double their level in the same period of 2024; in the month of March alone, pharmaceutical imports totaled an astounding $50 billion, with imports from Ireland alone reaching close to $30 billion—about fives times the (high) normal monthly total. Merck confessed to the Wall Street Journal that it had moved a year’s worth of supplies of its Irish-produced blockbuster drug Keytruda to the United States ahead of the tariffs.

But the best solution here isn’t to put tariffs on medicines. Tariffs can raise prices in the short term and the optics of raising the price of goods that save lives isn’t good.

The best solution is to get rid of the provisions of TCJA that (inadvertently) have created strong incentives to offshore production and profits so as to avoid paying the headline 21% rate. For the pharmaceutical sector, the 2017 tax law was Ireland first—not America first. That needs to be fixed. A well-designed fix would also create incentives to reshore other critical sectors, including the production of the equipment used to make semiconductors.

Step back a bit. America’s pharmaceutical companies have long been playing tax games. Before 2017, the big advantage of offshoring intellectual property and production came from the provision of the tax law that allowed firms to defer, indefinitely, profits earned offshore so long as those profits remained legally offshore. Pharmaceutical firms certainly took advantage of this provision—of the thirty companies with the most “cash” stashed offshore in 2016, nine were pharmaceutical companies. But even under this system, most pharmaceutical companies still paid some tax in the United States. AbbVie is a case in point. It produced its most profitable drug in Puerto Rico and had placed the right to profit from that drug in its subsidiary in Bermuda, so it had no reported U.S. earnings. But in order to cover the ongoing costs of its U.S. operations, it had to regularly repatriate funds from Bermuda—and it paid a (high) 35% rate when it did so.

This system of tax deferral also wasn’t quite the same as treating profits as permanently “untaxed.” As part of the transition to the new TCJA system in 2017, legacy profits held offshore were taxed at a 15.5% rate—so-called “deemed” repatriation—as the profits were considered to have been returned to the United States at that rate, and thus the deferred tax liability was automatically settled before the new tax system took effect. This was by design.

The Republicans who crafted the 2017 tax law, passed along party lines through budget reconciliation, likely assumed that bringing the headline tax rate down to 21% would incentivize U.S. firms to return home. The Democrats who pushed for global tax reforms through the OECD’s base erosion and profit shifting provisions certainly hoped that making it more difficult for firms to stash profits in zero-tax jurisdictions would have that effect. But the intersection of the incentives created in the 2017 tax code and the Democrats’ base erosion approach has been perverse—it has encouraged U.S. firms to locate both production and profits in low-tax OECD jurisdictions rather than the United States—most notably in Ireland.

The 2017 tax law effectively created three tax rates for U.S. firms: a 21% headline rate on domestic profits, a special 13.125% rate on profits derived from exporting intellectual property held in the United States (foreign-derived intangible income), and a 10.5% tax rate on global intangible income (GILTI). Big firms with large global profits faced a choice. Some companies that could—including Google/Alphabet, Nvidia, and Qualcomm—closed down their offshore subsidiaries in the Caribbean and Singapore, located the right to profit from their intellectual property in the United States, and took advantage of the special—and low—13.125% tax rate on profits from their global sales. But the choice between repatriating offshored intellectual property and moving it to a country like Ireland was a close one: Apple and Microsoft, for example, kept the right to profit from most of their non-U.S. sales abroad and took advantage of the even lower 10.5% rate on global intangible income.

The pharmaceutical sector didn’t really have the option of bringing its intellectual property home and getting the 13.125% tax rate because, well, most of its revenues are derived from sales in the United States. The big pharmaceutical firms all kept their intellectual property and production abroad, and exploited the low “GILTI” rate.

It bears emphasis that the large pharmaceutical firms could only access the low global minimum rate so long as they produced abroad. A firm that has its headquarters in the United States, keeps its intellectual property onshore, and produces onshore for sale in the United States would clearly be taxed at the 21% headline rate. A firm that shifts the right to profit from its intellectual property to an offshore subsidiary and produces its pharmaceutical ingredients abroad would attribute all of its profits to its offshore subsidiary, and thus would be able to—in theory—cut its U.S. tax rate in half, to 10.5%.

Three pieces of evidence show how this corporate flight from the U.S.—and with it, the loss of the U.S. tax base—happened.

First, the world’s firms—in the face of reforms through the OECD that made it difficult to continue holding their intellectual property in zero-tax jurisdictions in the Caribbean—moved huge sums of “intangibles” to Ireland. Ireland was in the EU and the OECD but had a low overall tax rate and, as importantly, a very generous tax regime for “intangibles.” Aidan Reagan of University College Dublin has shown that over $1 trillion in “intangible” assets migrated into Ireland in the past few years (more than making up for the depreciation of legacy assets over time).

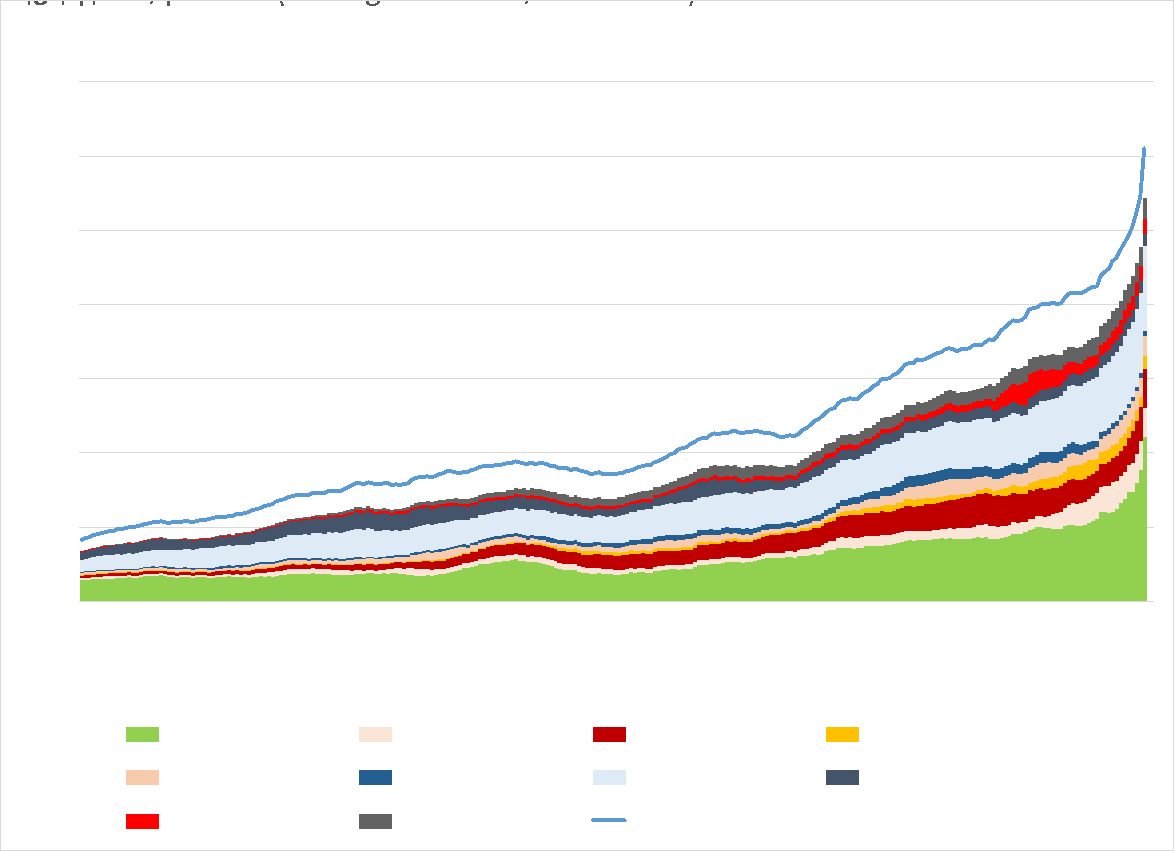

Second, the amount of pharmaceuticals that the U.S. imports from low tax jurisdictions like Ireland, Belgium (which has a special tax regime for pharmaceuticals), and Singapore soared. Total imports rose from just under $115 billion in 2015 to $250 billion in 2024. Most of those imports actually come from U.S. firms producing abroad to avoid U.S. tax—a good rule of thumb is that imports from Ireland and Singapore are from U.S. firms, while imports from Switzerland tend to reflect profit shifting by European firms. Note that the scale of these imports increased radically in 2024, as Eli Lilly started to produce its weight loss drug in Ireland, and that there was an additional spike in imports in early 2025 as a result of tariff front-running. Note as well that these imports are coming from high-wage countries—not low-cost countries—and they in no way help lower pharmaceutical prices. Rather, the imports come in at high prices designed to shift the profit on drugs whose pricing is protected by a patent to an offshore tax center.

And third, American pharmaceutical companies stopped paying corporate income tax in the United States. Or to be clear, they stopped setting aside any of their current profit to pay U.S. tax. Some are still paying off their tax liability from the “deemed” repatriation of 2017, so their lobbyists can accurately say that they do still make some payments to the U.S. Treasury. But their own disclosure shows that they aren’t setting aside any funds out of current earnings to pay their expected 2024 tax to the U.S. Treasury—because they don’t expect to pay any.

In 2023, the top six pharmaceutical firms set aside zero to pay U.S. federal corporate income tax while paying about $7 billion abroad (on a global profit of $70 billion). In 2024, the top six had a tax loss in the United States while paying close to $12 billion in tax outside the United States. American taxpayers were, in essence, subsidizing these companies.

The two main political parties in the United States are unlikely to agree on the right corporate tax rate. But there should be bipartisan agreement that U.S. companies should pay tax in the United States rather than in Ireland or Singapore

Recognizing that the 2017 TCJA tax reform—the extension of which is currently under debate on Capitol Hill—isn’t perfect is the first necessary step. The current House Ways and Means Committee proposal would just extend the 10.5% global minimum tax without any reforms. That guarantees continued tax avoidance and a world where American firms shift profit on U.S. sales out of the United States—at least in the absence of permanent tariffs. It reduces the number of well-paid production jobs in the U.S. biopharmaceutical sector, makes U.S. supply chains more vulnerable, and deprives the U.S. Treasury of billions of dollars of needed tax revenue.

Agreement on the specific ways to fix that is the second needed step. A narrow, but effective, fix for the pharmaceutical industry would be to just deny the low 10.5% tax rate to profits derived from U.S. sales. A broader fix, which would also address profit shifting by the large “tech” companies, would both raise the tax rate on global intangible income and penalize firms for shifting intellectual property developed with the help of U.S. tax incentives out of the United States. Making the transfer of valuable intellectual property among the offshore subsidiaries of a firm a taxable event in the United States would also help; companies now sell their intellectual property to themselves so as to generate inflated depreciation allowances in Ireland without facing a U.S. tax penalty.

The details get complicated, but there should be agreement on one point—a tax policy that discourages U.S. production and that has reduced tax collections by the United States while increasing tax collections abroad doesn’t serve any American interest. American pharmaceutical companies have moved the profit on drugs that were developed in the United States, often with an assist from research supported by the National Institute of Health, to offshore subsidiaries that don’t pay income tax in the United States. And the profit on drugs developed in the United States and sold to U.S. taxpayers now often isn’t taxed at all in the United States. Such egregious tax avoidance is an enormous affront to the American taxpayer—and it can and should be stopped.